Logging Considered Harmful

Hi, I’m David and in this post I’m going to share some experiments I created to show some rather surprising things about race conditions and log statements in iOS and Android apps.

I write my apps in C# using Xamarin but the concepts I’m going to talk about here apply equally to apps written in Objective-C, Swift or Java.

Off to the Races

What’s a race condition?

According to the fount of all knowledge

Race conditions arise in software when an application depends on the sequence or timing of processes or threads for it to operate properly.

Race conditions are embarrassingly easy to create. Here’s some C# code that has a race condition:

var result = 100;

var expected = 93;

var workerCount = 15;

var workers = Enumerable

.Range (0, workerCount)

.Select ((x) => {

return Task.Run (() => {

result += x % 2 == 0 ? -x : x;

});

})

.ToList ();

await Task.WhenAll (workers)

.ContinueWith ((t) => {

if (result != expected) {

// race detected!

}

});

Before you ask, I wrote this code on purpose to make a point. This is most definitely not production-quality code. However, it is representative of the kind of problems that occur in buggy multi-threaded code.

If all the tasks operate in sequence, the final value of result is always 93.

However, as written, this code will not always end up at that answer, because some Tasks may run in parallel on the .NET thread pool, and the order of the calculations can vary. This is especially true if the CPU has more than one core, because the operating system can allocate threads to separate cores.

It is therefore highly likely that the final value of result will not be the one we expected.

It’s a Fix!

Suppose I told you I could cure the race condition in this code by adding just one line of new code?

And that this new line of code doesn’t do anything useful?

However unlikely it may seem, it’s actually true. I can fix the race condition with one line of code:

var result = 100;

var expected = 93;

var workerCount = 15;

var workers = Enumerable

.Range (0, workerCount)

.Select ((x) => {

return Task.Run (() => {

Console.WriteLine("worker {0}", x); // blink and you'll miss it!

result += x % 2 == 0 ? -x : x;

});

})

.ToList ();

await Task.WhenAll (workers)

.ContinueWith ((t) => {

if (result != expected) {

// race detected!

}

});

If you run this code in a .NET app you’ll get a consistent answer: 93 every time.

That seems very odd. What’s going on?

Cooking the Books

In the .NET documentation I found this little gem:

I/O operations using [System.Console] are synchronized, which means multiple threads can read from, or write to, the streams.

Synchronised in this context means uses locks to ensure safe access to a shared resource by multiple threads.

In other words, the mere fact of including Console.WriteLine in my code has automatically introduced synchronisation, because Console.WriteLine’s implementation is itself synchronised. (Now that .NET’s source is freely available, you can verify this for yourself here, which if you drill down ends up here).

It’s this that fixes - or rather, hides - the race condition: it imposes just enough order on the Tasks as they execute that they end up executing one at a time, instead of all mashed up together.

Other languages and environments have the same problem. As an experiment, I re-wrote the C# code here in Swift, Apple’s new language, replacing Console.WriteLine with Apple’s own NSLog, and observed much the same result.

The Apple documentation says this about NSLog:

Output from NSLogv is serialized, in that only one thread in a process can be doing the writing/logging … at a time. All attempts at writing/logging a message complete before the next thread can begin its attempts.

It’s basically the same deal as with Console.WriteLine in C#. With NSLog statements inserted, the race is often (but to a much lesser extent than with Console.WriteLine) hidden, and the answer is almost always consistent. Without logging, the race re-appears, and it’s anyone’s guess what the answer will be.

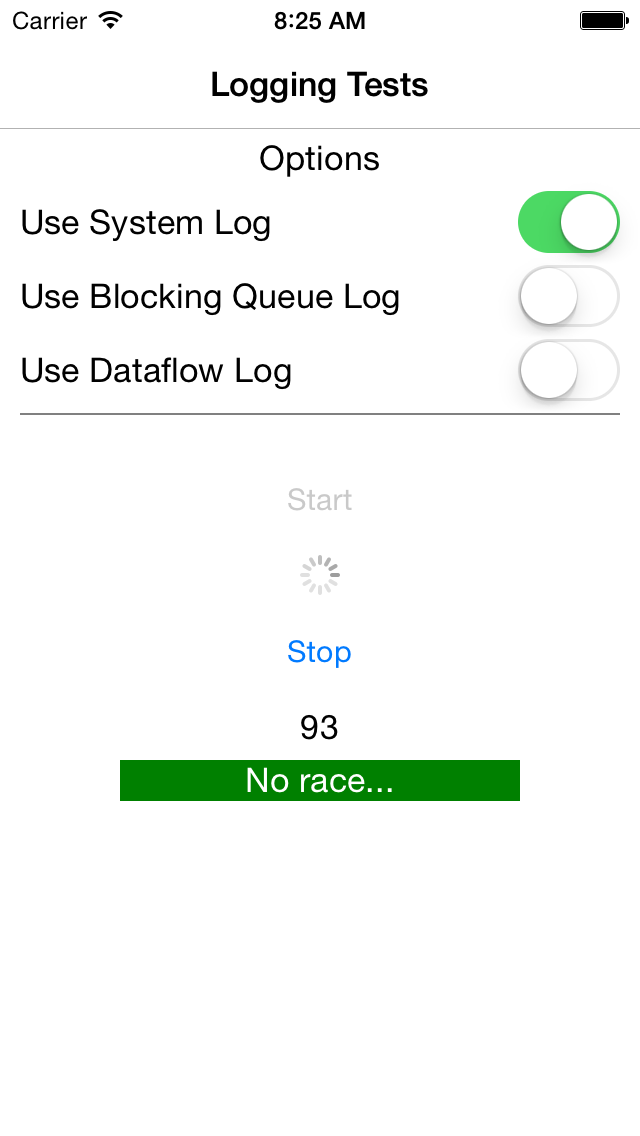

By the way, these preliminary results were obtained using a relatively old MacBook Pro running the iOS simulator. To test the situation more thoroughly I built several versions of the code in different environments. The screenshots below show the C# app in action on iOS and Android:

Screenshot 2.png)

|

I’ll be discussing the app and the logging code it contains in more detail in a future post.

To test the effect of logging on this simple calculation, I tried various other combinations of hardware and software and achieved broadly consistent results. The combinations included:

| Language | Environment | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C# | Android phone app | The code won’t race on the Xamarin Android emulator. However it does race on my test hardware (Samsung Galaxy 4). Logging with Console.WriteLine does not always hide the race. |

| C# | Android tablet app | The code won’t race on the Xamarin Android emulator, or on my test hardware (Google Nexus 10). Other hardware may perform differently. |

| C# | iPad app | On the simulator the code races, and the race is hidden by Console.WriteLine logging. On my test hardware (iPad 2) the code races, and logging with Console.WriteLine hides the race. |

| C# | iPhone app | On the simulator the code races, and the race is hidden by Console.WriteLine logging. On my test hardware (4S and 5S) the example code won’t race, even without logging. |

| C# | Windows 8.1 Command Line program | On test hardware (Intel Core 2 Duo Windows 8.1), I needed 20000 workers to make the code race. Adding Console.WriteLine to the worker code hid the race very consistently. |

| Objective-C | Mac OS X Yosemite Command Line program | On test hardware (MacBook Pro 17”), I needed 20000 workers to make the code race. Adding NSLog to the worker code hid the race most of the time - not always, but certainly often enough to be a real problem. |

| Swift | iPhone app | On the simulator, the code races, but the race is hidden by NSLog logging. On test hardware (4S, 5S) the code races, and the race is not hidden by NSLog logging. |

It’s obvious from these results that the power of the computer has a significant effect on whether the race occurs. On a desktop PC or laptop, I needed significantly more workers to make the code race compared to phone or tablet hardware. Interestingly, on iPhone 5S and Nexus 10 hardware the Xamarin-compiled C# code refused to race at all.

The source code for all of the test applications will be available shortly.

Conclusion: Caveat Logitor

That’s just my poor pig-Latin for: if you have a race condition in your code, almost the worst thing you can do is sprinkle log statements around to try and figure out what’s going on, especially if your logger uses locks to make itself thread-safe. You might inadvertently hide the race condition by adding the logging.

Even more chillingly, some loggers are removed from release-mode code by the compiler. Therefore you could create a program that works when it’s being developed (because the log statements everywhere hide any races) and fails horribly when run on a user’s device (because there are no log statements to hide any races).

The right way to fix code that has a race condition is to fix the race.

In my next post I’ll present a logger that doesn’t accidentally fix race conditions, which makes it safe to use when debugging races.

Stay tuned for more threading exitement next time!